K2-18 b: A Carbon-Rich Planet with a Methane-Dominated Atmosphere

About 124 light-years away from Earth lies the planet K2-18 b. This exoplanet orbits its star in the “habitable zone,” where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist. Orbiting a red dwarf star, K2-18 b is larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune, with average temperatures around 300K, or 80 °F. It is often referred to as a “sub-Neptune” (see Figure 1). These planets are among the most common in our galaxy, yet their nature remains poorly understood. As a potentially life-friendly world, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) Cycle 1 GO Program 2722 lead by personal investigator Nikku Madhusudhan, brought K2-18 b back into the spotlight, bringing better insight into the actual composition and structure. The observations of the planet’s atmosphere revealed a surprising chemical composition that is dominated by methane (CH₄) and is much more rich in carbon than expected.

Figure 1: This artist’s impression shows what K2-18 b, a planet about 8.6 times more massive than Earth, orbiting a red dwarf—a cool, small star—might look like based on scientific data.

Credit: Illustration: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

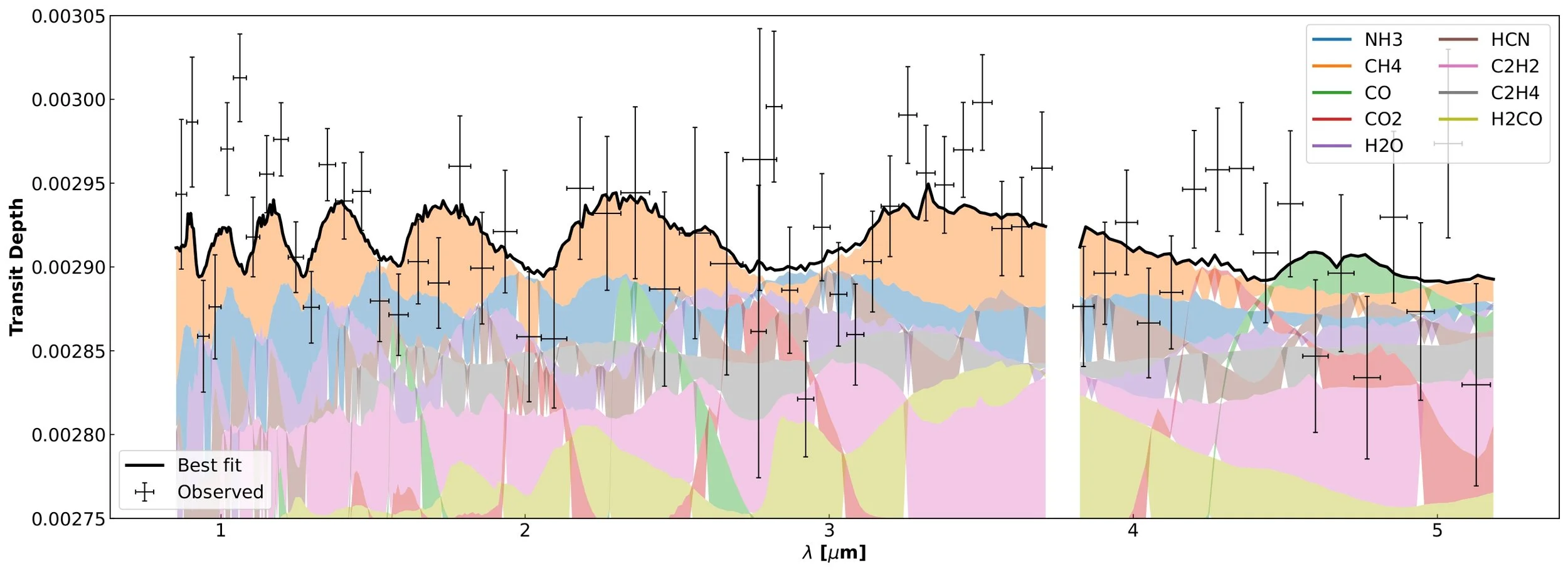

Dr. Adam Y. Jaziri from the LATMOS laboratory in France and his colleagues used an advanced chemistry model, called FRECKLL, to interpret the JWST observations. Jaziri and his colleagues' findings are striking. Methane is robustly detected in the planet’s atmosphere, dominating the spectral features (see Figure 2). Earlier studies had already confirmed methane in the planet’s atmosphere, but the new analysis goes further. They find that the atmosphere has an unusually high carbon-to-oxygen ratio, meaning it is far more carbon-rich than expected. This imbalance offers important clues about how the planet formed and how its atmosphere has evolved. The imbalance creates conditions that encourage the formation of complex carbon-based hazes, similar to those thought to have existed on early Earth.

In carbon-rich environments like this one, methane and other hydrocarbons can be broken apart by stellar ultraviolet light, allowing their fragments to recombine into long carbon chains that accumulate as tiny solid haze particles. Laboratory studies and atmospheric models show that this process becomes especially efficient when oxygen-bearing molecules, such as CO2 or H2O, are scarce, because oxygen tends to reduce haze formation by oxidizing hydrocarbons into smaller, stable gases that no longer stick together to make particles. In other words, an atmosphere dominated by carbon and hydrogen, but with relatively little oxygen, naturally favors the growth of complex organic hazes, much like those seen on Titan, a moon of Saturn.

Figure 2: Main molecular contributions (shaded areas) to the JWST observations of K2-18 b (Madhusudhan et al. 2023) from the best-fit non-equilibrium 1D model. The total model is shown as a solid black line. This highlights the dominant contribution of CH₄ and the presence of minor, less visible species.

Jaziri and his colleagues also looked for three other common atmospheric gases, CO₂, H₂O, and NH₃, but didn’t detect them. That doesn’t mean they aren’t there; their signals are simply too faint and overlap with methane, making them hard to pick out. These gases matter because each would reveal something different about the planet: CO₂ helps trace heat and atmospheric chemistry, H₂O can hint at temperature and humidity, and NH₃ can offer clues about deeper layers or even the presence of oceans. Detecting them in the future would give us a much clearer picture of the planet’s environment.

This study shows that by combining observations from state-of-the-art telescopes with advanced numerical simulations, astronomers can unravel the chemistry of distant planets. In particular, thanks to JWST’s ability to probe planet atmospheres, K2-18 b has moved beyond being just a candidate for habitability studies. It is now a laboratory for exploring exotic atmospheres. Its carbon-rich, methane-dominated composition challenges simple expectations for sub-Neptunes. Future observations with JWST, as well as future ground-based facilities like the Extremely Large Telescope’s ANDES instrument, will help to confirm the presence of other minor species in the planet’s atmosphere.

This article made use of the following publication:

Jaziri A. Y. J. et al. 2025, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 701, A33

Original Contributor

Dr. Yassin Jaziri

Laboratoire Atmosphères & Observations spatiales (LATMOS)

Dr. Yassin Jaziri is postdoc from the Laboratory for Atmospheres, Environments, and Space Observations (LATMOS) in Paris, working on the modelisation and characterisation of exoplanetary atmospheres.

Editors

Mélisse Bonfand

Science Editor

Annika Geiger

Senior Editor

Brielle Shope

Editor-in-Chief